Among talented chefs and ardent gastronomes, Japan is a desirous destination, every bit as much as France, Spain and Italy. Also interest in Japanese cuisine has swiftly grown in recent years as seen by the number of Japanese-inspired and Japanese fusion restaurants around the world and the migration of chefs from Japan to Paris and the East and West Coasts of the United States. Nothing, however, surpasses going to Japan itself, something I have been doing for business and vacation since the early 1980s. Yet so varied, rich and overwhelming is Japan’s gastronomic landscape that I have much of it left to visit. Still, what I have experienced is unforgettable, and the reason that I put forth this essay (partly based on a recent 17-day visit that included a spectacular three-day art visit in the Seto Inland Sea)  as part primer and part impressions of specific addresses is to make you to think twice about what to see soon in your forthcoming travels.

as part primer and part impressions of specific addresses is to make you to think twice about what to see soon in your forthcoming travels.

Why the idea of going to Japan meets with reluctance for so many people is tied up in language, customs, and a misconception about the cost. It’s true that the percentage of English-speakers among the Japanese is noticeably less than in European countries, but made up for by everyone you meet bending over backwards to lend you a hand whenever you need one. We Westerners also worry about making frequent social or culinary faux pas such as drinking sake when eating rice or sticking your chopsticks straight down into your bowl of rice (It’s funereal), and that some of the meals in the prestige restaurants will equal in cost those of the most-expensive restaurants in Western capitals, which can be offset by cheap delicious meals other than ratings-driven sushi or kaiseki ones and staying in comfortable, if not luxurious, affordable hotels. In the end, if you are willing to devote many hours of planning your trip and being adventurous, you will likely end up being a confirmed Japanophile, waiting and hoping to return in the not-too-distant future.

Trip planning for Japan is arduous, time-consuming and frustrating, yet also engaging and even enjoyable, Your fingers will have a good workout shuffling between the restaurant websites such as Trip Advisor, Tabelog, Gurunavi and Michelin; the hotel and hotel reservation sites; and the myriad guidebooks and websites about where to go and what to see. There are scores of food blogs you should look at, but many of them are poorly written by people who you don’t know if you can trust. So in the end, it is like everywhere else: hit or miss, but with what I believe is more hits than misses. Still, intuition or hunch is what will drive a lot of the decision-making. The best is to have knowledgeable friends in Japan or see how a restaurant scans by bringing it up on three or four websites. Michelin can be good for narrowing down the field, but as I state below, it misses some of the best addresses. (My restaurant search always begins on Mouthfuls where there are a few people who go to Japan often, with the most experienced being “Orik”, Ori Kushnir.)

Absent a Japanese food-loving friend, your next best one is a team of hotel concierges. They will work hard for you and report back on the reservation results within a day or two, as well as manage your reservation book, moving reservations around, working out your dining schedule and dealing with your changes of mind. The better the hotel you stay in, the better the concierge service should be. Since the first time I visited Tokyo, my hotel of choice has been the Okura. I think of it as the home away from home for artists, musicians, and hip travelers due in part to its architecture and design, the earliest and best part of which met the fate of the wrecking ball to make room for a 41-story tower planned for completion nine or ten months before the 2020 Olympic Summer Games. Still, the South Wing has a gorgeous two-story-high lobby, bedrooms a notch below hotels twice the prices, but in the same 5-star luxury category, and a fine concierge staff that is better answering e-mails than face-to-face in the lobby.

If I had to choose one near-universal factor that sets apart eating in Japan, it would be size. By now you must have encountered the line about Tokyo having the most restaurants with Michelin stars (194, 75 or so of which are French, Italian Spanish or Chinese) of any city in the world. It is for the simple reason that restaurants in Japan are small, which is why the website Tabelog is able to provide information and photographs from more than 130,000 in Tokyo alone, even though 99% of them wouldn’t interest a non-resident.

Most everything else in certain kinds of Japanese restaurants is small. Many chefs have a small number of assistants; and the kitchens are small, as is the number of cooking appliances. Most significant, small portions are what characterize the most glorified cuisine in Japan: Kyoto or kaiseki, although the number of courses number a dozen or so. This category along with sushi shops account for the plurality of restaurants with Michelin Guide stars.

As much as I disdain all the Michelin guides covering the Western world, it’s even worse in Japan, Tokyo in particular. Forget the opacity and the unknown degree of credentials of the anonymous people who inspect the restaurants and/or administrate the guide. What the primary and pernicious result is that it makes it all but impossible to visit some of the small, highly-rated restaurants (in Kyoto as well) on relatively short notice unless you have the right connections or extraordinary luck. In fact, some restaurants state that they are fully booked the rest of the year while others only serve dinner. Then for whatever reason, certain great restaurants are omitted altogether from the guide including the Tokyo restaurant I liked the most in my 2014 visit, Matsukawa, and the one on my recent trip, Kasumicho Suetomi.

Once you turn your attention and aspirations from the three-star establishments to those with two stars, you enter a zone of increased uncertainty While I enjoyed all such rated restaurants in Osaka, Kyoto and Toyama, two of the four two-star restaurants I visited in Tokyo were money down the drain; another was uninspiring, but acceptable, and the fourth gave my wife and me one of our best kaiseki meals.

I found in a few of the restaurants in Tokyo, and no place else I visited, a sense of disdain, if not discrimination, against Americans, specifically, and perhaps “gaijin” (outsiders) in general that even extends in on rare occasions to denying reservations or making you dine outside of prime time. In Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto, however, my hotel concierge desk sent me e-mails stating that wherever I booked, I had to arrive on time, cancel a day or two before to avoid being penalized the cost of the menu, and, perhaps like everyone, choose a menu by cost ahead of time. In some cases, not only would I be charged the cost of the menu for a tardy cancellation or not showing up, but a surcharge as well. Whether part of this was the hotel concierges’ doing or entirely the restaurant I have no way of knowing. At times, in Tokyo at the two-star kaiseki restaurant Seisoka and the sushi restaurant Ginza Harutaka , the treatment was so disdainful that my early attempts to create some rapport went out the window, as I simply stopped trying early in the meal. Both restaurants were as expensive as you would find anywhere, with Harutaka Ginza being the most disappointing with its no-choice omakase.

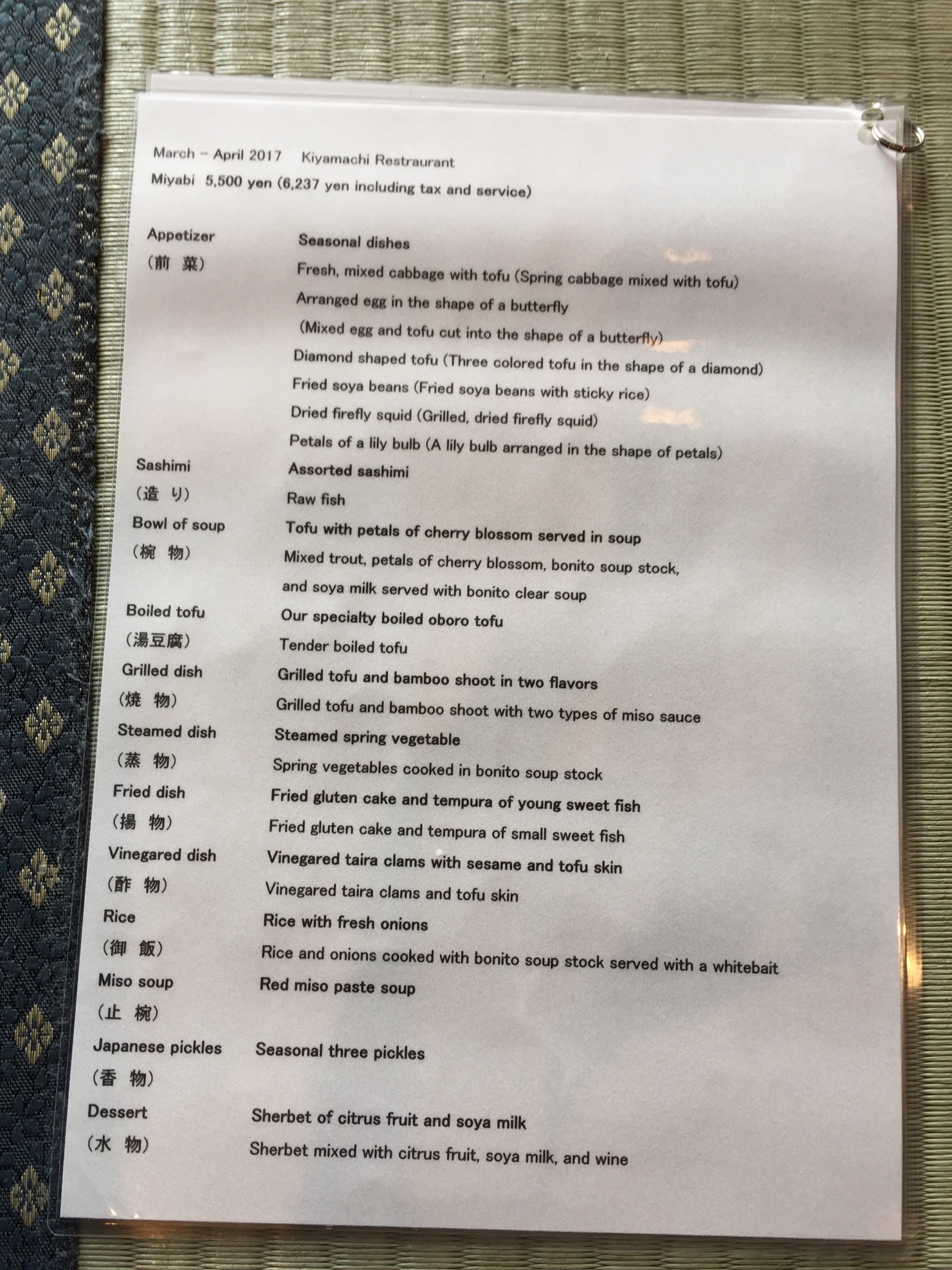

During my trip, I ate nothing except Japanese food except for a quasi-French meal at the Benesse House Art Islands French restaurant and dim-sum at the Okura Chinese restaurant. The Japanese meals were classic kaiseki; sushi/sashimi; teppanyaki; Kaiseki Buddhist vegetarian; Kaiseki with tofu dishes, tempura, okonomiyaki, soba and kappo or general Japanese cuisine. The plurality of my meals were kaiseki—ten of them–and in retrospect I had two or three too many. To partake in impeccable freshness and seasonality and the overwhelming variety of fish and vegetables (wild or mountain ones when I was there), kaiseki restaurants are where you will find them. After two or three such meals you will become attuned to the kaiseki format  in which a soup and/or sashimi and other appetizer precede fish and beef cooked in different ways followed by a vinegared dish, miso soup, pickles and, preceeding dessert, rice mixed with ingredients that included cherry blossoms (It was after all the height of the season in Osaka)

in which a soup and/or sashimi and other appetizer precede fish and beef cooked in different ways followed by a vinegared dish, miso soup, pickles and, preceeding dessert, rice mixed with ingredients that included cherry blossoms (It was after all the height of the season in Osaka) white shrimps that are unique to Toyama; and my favorite, turtle eggs at Kasumicho Suetomi in Tokyo. Certain ingredients appeared in a few or more restaurants. Desserts were invariably fruit-based such as mango,

white shrimps that are unique to Toyama; and my favorite, turtle eggs at Kasumicho Suetomi in Tokyo. Certain ingredients appeared in a few or more restaurants. Desserts were invariably fruit-based such as mango,  strawberries and melon. Fresh bamboo was ubiquitous. In Tokyo, we encountered octopus sushi a few times, while in the fish department nodoguru or black-throated sea perch and modai or seabream were the cooked fish of choice overall. Many vegetable dishes were garnished with miso paste, and Japanese dumplings in soup made an appearance in most of the meals but with different fillings, including cherry blossoms. Fugu or blowfish milt, (shirako) ,

strawberries and melon. Fresh bamboo was ubiquitous. In Tokyo, we encountered octopus sushi a few times, while in the fish department nodoguru or black-throated sea perch and modai or seabream were the cooked fish of choice overall. Many vegetable dishes were garnished with miso paste, and Japanese dumplings in soup made an appearance in most of the meals but with different fillings, including cherry blossoms. Fugu or blowfish milt, (shirako) ,  the sperm sac, which appeared several times is even an acquired taste for some Japanese, A lot of the taste depends how it’s cooked; it can be fried, steamed, boiled or grilled, and the sauce that accompanies it. The most palatable was the milt in yuzu sauce at Ebitai Bekkan in Toyama. Contrary to descriptions of sweetness and “oceanic”, the blowfish milt can be fishy and sour.

the sperm sac, which appeared several times is even an acquired taste for some Japanese, A lot of the taste depends how it’s cooked; it can be fried, steamed, boiled or grilled, and the sauce that accompanies it. The most palatable was the milt in yuzu sauce at Ebitai Bekkan in Toyama. Contrary to descriptions of sweetness and “oceanic”, the blowfish milt can be fishy and sour.

Devotees of tasting or dégustation menus will be right at home with kaiseki meals. Those of us who eschew them, however, can well argue that the two are conceptually dissimilar for good reasons. For one, you can’t argue against a class of cuisine that has been around for 700 years. Unlike Western tasting menus, kaiseki isn’t a contrivance. It is derived from the tea ceremony, not some recent economic model designed to save costs in every aspect of managing a restaurant. It also has a seasonality and freshness rigor on a level that is exceedingly rare. While both emphasize presentation, kaiseki decoration is derived on decorated, well-crafted ceramic and lacquer ware, sometimes old and rather valuable, and adding around or on top of the foodstuff itself leaves, flowers and other natural decorative elements.  Tasting menu purveyors, on the other hand, engage in what I call sliceydicydribbydrabby or “potchkying” with the food itself, with chefs bending over with their tweezers, squirt bottles, and paint brushes ending up with what is invariably edible kitsch.

Tasting menu purveyors, on the other hand, engage in what I call sliceydicydribbydrabby or “potchkying” with the food itself, with chefs bending over with their tweezers, squirt bottles, and paint brushes ending up with what is invariably edible kitsch.

As it is for restaurant food in general. the success or appeal of a kaiseki meal depends on the chef, the restaurant, the quality and the type of food. In Kyoto we had two kaiseki meals that differed from the others because one specialized in tofu dishes and the other was a vegetarian meal in a Buddhist temple. The season, too, has to be a factor. For me the prospect of visiting some kaiseki restaurants in November and December during the height of the season for crabs, oysters and fugu is tempting.

( Part Two, in which I touch upon specific restaurants, will follow soon